My father passed away in May 2017 at age 86. Until the last year of his life when he became ill, he was an insightful man and interested in the world and people around him. He used to tell stories of his childhood and youth during the Second World War in Europe. And now, as my teenage sons have been experiencing the seminal event of their young lives, I can’t help but wonder what he would have made of what is happening in the world today.

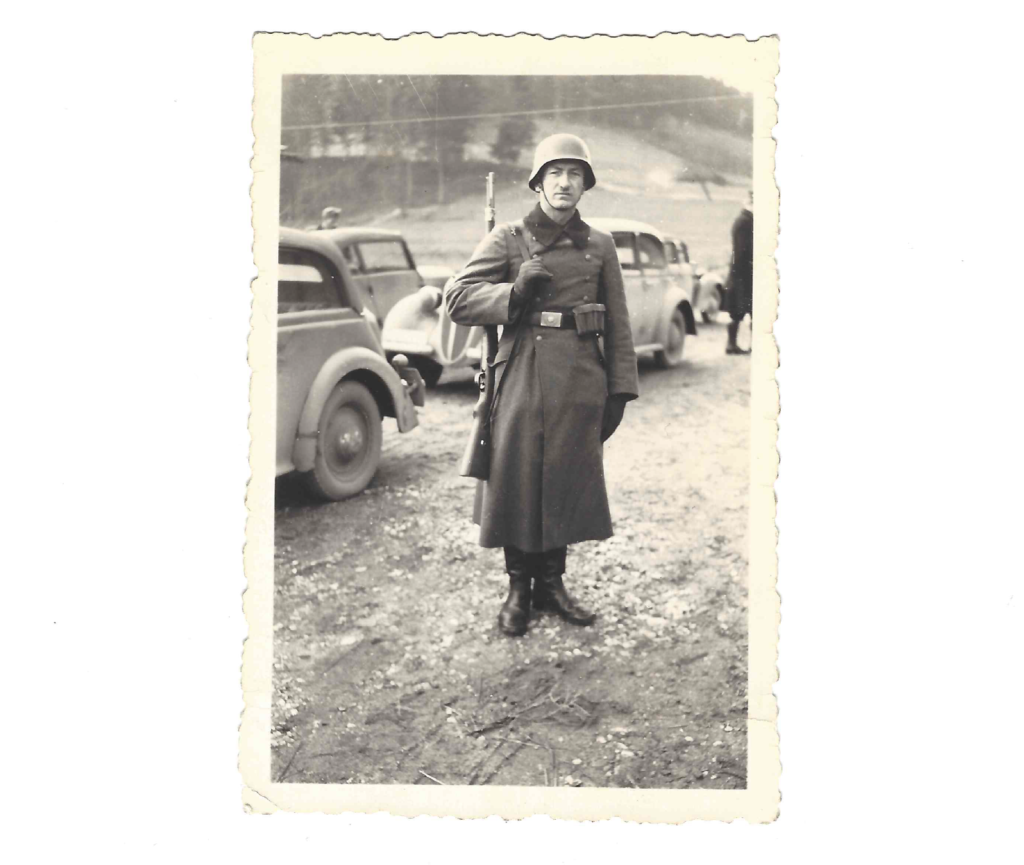

My father grew up in Germany, near the border with Poland, during the Second World War. He was two months short of his tenth birthday when the Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. He recalled all the soldiers and tanks gathering near his home in anticipation of the invasion that the Nazis were planning. Being a typical boy, he loved climbing up on the tanks, fraternizing with the soldiers and enjoying the chocolate they gave him. And then one morning, they were gone – Hitler’s Blitzkrieg had begun.

My grandfather was called up immediately, and my father and his father didn’t live together again for nine years. Fast forward to January 1945 and my father himself was conscripted at age fifteen (younger than my older son is now!) to go fight on the Eastern Front. The timing saved him from active combat, but he ended up in a displaced persons camp. He escaped and managed to reunite with his mother, who had fled their home for fear of the invading forces from the East. By that time, his part of Germany had been ceded to Poland, and he and his mother and her mother became refugees after they lost their home behind the new border. For three years, his family lived in East Germany before crossing to the West in 1948 (which is another story in its own right).

My father’s recollections of his experiences left an indelible impression on me. My mother (who is younger but also lived through the war in another part of Germany) had her own stories as well. Nonetheless, not until the past few months did I have an inkling of what they and so many others must have felt during the war – fear, uncertainty, a world turned upside down through no fault of their own. While there are thankfully no bombs about drop on my head nor have there been any soldiers anywhere to be seen (other than helping out in selected long-term care homes), for the first time in my life I experienced long lines at the grocery store, empty shelves, panic buying and shortages of select items. It was a strange feeling and the instinct to hoard, or at least over-purchase, was hard to resist. People were borderline aggressive in snatching items off the shelves and while standing in the now ubiquitous line ups, initially inside the grocery stores and later outside as well. It brought to mind the expression, “When the watering hole gets smaller, the animals get meaner.”

I must confess to having bought more than I usually would have – mostly because I was concerned that when I needed an item down the road, it wouldn’t be there. So, yes, I laid in a small inventory. And the truth is, I have learned that fear is contagious and also discovered how easy (and irrational) it can be to follow the herd. Fortunately, despite the panic buying, for the most part many items remained available throughout the depths of the self-isolation period. Some items, such as toilet paper, have recently begun to reappear and remain on shelves, although certain cleaning supplies remain scarce. Overall, however, it seems that, at least for now, the “supply lines are holding”. Fortunately, food security has not been an issue in my household (although I realize others have not been so fortunate), but I have also come to appreciate that money becomes essentially worthless when a needed item is simply not to be had (think flour, sugar and yeast).

I expect my father would be able to understand my impulses to buy extra food, although far more viscerally than I have experienced them. He often spoke of going hungry in the post-war years while living in East Germany: he and his mother would pick through the farmers’ fields after the harvest had been taken in with the hope of finding a stray potato or two that had been missed. He also told the story of his father sending a special parcel to them from West Germany, where my grandfather had gone on ahead alone to prepare a new life for his family. The parcel contained only potatoes, but my father always said that it was the best gift he ever received. To his dying day, my father could not abide wasted food.

In our present situation, there has also been the issue of the continuing battle to secure medical essentials – personal protective equipment, testing kits, hand sanitizer. Early on liquor producers turned to making hand sanitizer and manufacturers have worked to retool their factories in order to produce medical necessities like face shields for frontline workers. At least we have not had to produce tanks or bombs, like in my father’s day. Today’s scientists are working on research to find new treatments and develop a vaccine, not unlike the engineers who once worked on making faster planes or the doctors who pioneered new medical techniques for repairing broken bodies.

These are the parallels in my father’s and my experiences, but there the similarities end. Ours is a peacetime conflict. Our enemy is a microscopic virus – something we cannot see, something we cannot so easily vilify in the guise of a foreign face or a propaganda poster.

I count my blessings daily that I am not expected to send my sons off to war. Instead I can hold them near and dear by keeping them at home with me: admittedly we are all a little tired of the overexposure to each other’s company, but at least I know where they are and that they are safe. Like my father, their schooling is currently falling away. Unlike my father, the miracle of modern technology has given us the possibility of at least staying somewhat connected to their education. In the meantime, the “bravest” thing I can do is to separate my children from their friends and prevent them from boarding public transit. Instead my grandmother had to send first her husband and later her underaged son, her only child, off to fight.

This war is being fought primarily on the medical front in the hospitals and long-term care homes, where our medical staff are our modern soldiers. Then there are all the equally exhausted grocery and pharmacy workers, truck and delivery drivers, civic workers who collect garbage, run the water treatment plants, deliver the mail and keep the lights on, to name but a few of the people keeping our 21st century life moving. These are the heroes of our war effort and, like the soldiers in my father’s war, they will likely pay the price of mental health issues when they can finally rest again.

I, for my part, have stayed home and thereby “done my civic duty.” It is a strange thing to find doing “nothing” is actually making a contribution to our war. The best I can offer is to continue to keep my little family safe and functioning by preparing meals, doing laundry and keeping my kids feeling secure as their world too turns upside down. Until recently I had always been perplexed by the fact that during the First World War women seemed to be constantly knitting socks to send to the soldiers at the front. The understanding finally dawned on me: it was their way of feeling useful and contributing to the war effort in their own small way. I get it now.

My father’s conflict is called a “world war”, but our war on this illness deserves that moniker as well. This pandemic is continuing to cut through countries around the whole world. No continent or nation will be spared, although admittedly some countries are coping far better than others. Nonetheless, this virus knows no boundaries and neutrality is no protection. It truly is a world war.

Ours is an invisible peacetime war that my father likely would have had difficulty understanding. He would recognize the war effort, but he would not understand the unseen enemy or the fact that our world is being held together by a thin thread called the internet. I expect he would have found our fear of this microbe ridiculous given what he and his generation lived through and, being a highly gregarious soul, would have suffered greatly under the demands of self-isolation. I’m relieved he doesn’t need to experience this modern conflict. Rest in peace, Dad.

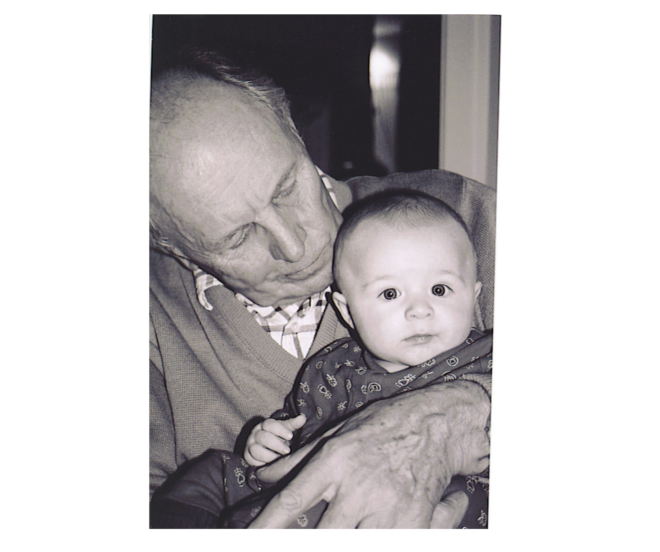

Featured Photo: My father with his first grandson, February 2004 (Photo Credit: Sue B.)

A lovely story, connecting your father with our current crisis. A wonderful read on Father’s Day.

Thanks, Monica. I expect your father had a few stories about his childhood in Europe as well. Happy Father’s Day to your husband.

A wonderful read!

Thanks, Jane! Glad you enjoyed it.

Enjoyed your interesting and insightful story. I too lost my wonderful dad a few years ago at age 93. He was in the Air Force and I recall his stories. I also wonder what he would have thought about this pandemic. I also lost my incredible nephew a few years ago at age 22. He was a genius working at GOOGLE. Our family wonders how he would have coped. So many thoughts during this historical time!

So sorry to hear about both your losses, Shelley. Terribly sad about your nephew – cannot imagine (every parent’s worst fear). I too have been thinking about the longer-term effects of the present situation on my kids. We are all muddling through as best we can. …

Always admired the Japanese and try to follow their principles. In spite of a nuclear fuel leak, they never resorted to panic buying and hoarding !

On my part, I had told myself. Let the liquid soap vanish. I will use soap bars ! Those who did, did not perish from cross infection within their families !

Kudos to you that you resisted the temptation to overreact, Mujib. Cooler heads prevailing in such situations is always a good thing!

A well written tribute to your father brought together in different times of adversity.

Thanks, Heather. It really has been a strange/interesting time and I wish I could discuss the situation with my father.