After my parents moved from St. John’s, Newfoundland to Toronto in July 2009, my father was quite lonely. I only discovered after he moved to Toronto how incredibly extroverted he was and how much he missed his friends and social network at home. He made his best efforts to get to know new people and make new friends. Sadly, due to his age (then 80), many of the new acquaintances he made either moved away into some sort of assisted living or passed away, leaving him more isolated than ever.

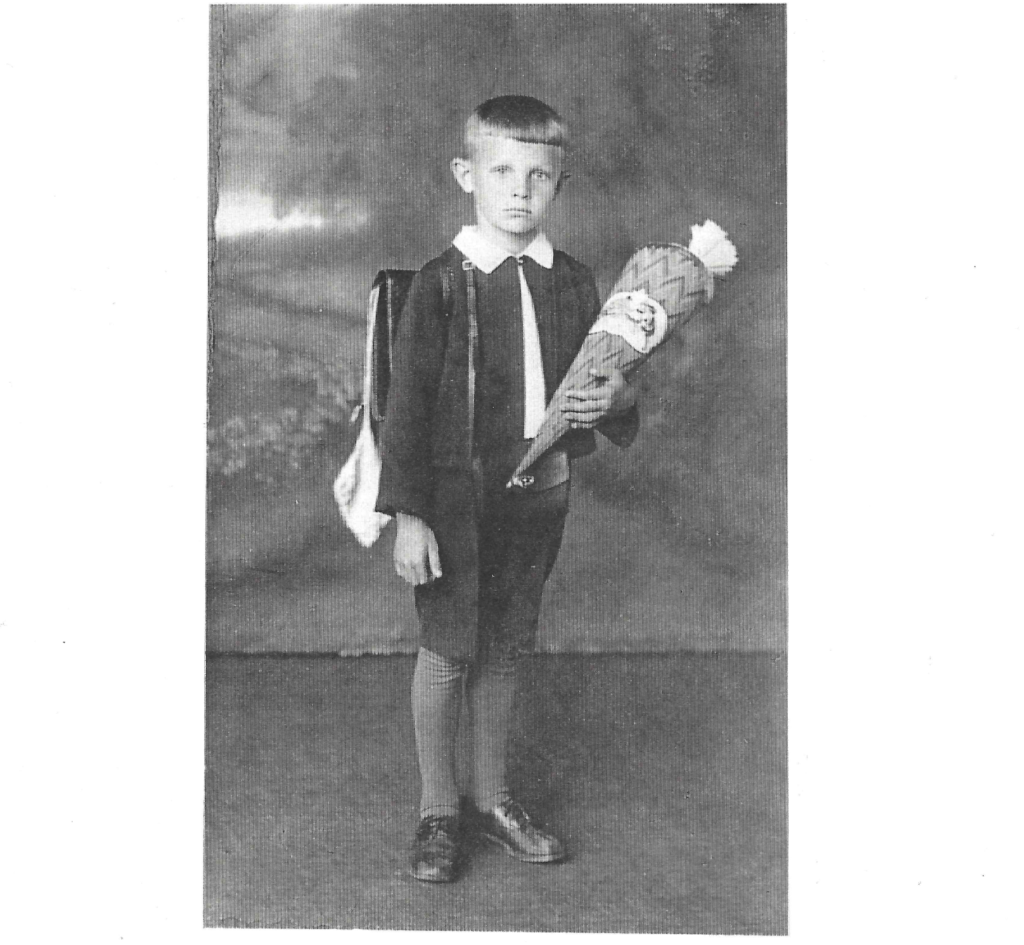

To help combat his loneliness and give him a continued sense of purpose, one of the tasks he set himself was to write his “life story,” as he liked to call it. It is amazing compilation of memories of his childhood in pre-war Germany, his experiences during World War II, and his life in Canada after he immigrated to this wonderful country in 1957. His memoirs are a lasting gift to his daughters and grandsons. I only wish I’d had more time and energy to devote to asking him for additional details and clarification before he left us in May 2017. I miss him.

On the occasion of Father’s Day 2021, I thought I would share some of his reminiscences of a time and place now lost in history (unbelievably coming up to almost a century ago). The excerpt I have chosen contains some of his recollections of village life before the Second World War. I have done some minor editing, but tried to preserve my father’s voice, which I hear strongly when I read his writing. I think my father would have been thrilled to know that his memoirs were published online by his daughter. I hope you enjoy them.

Following the First World War, the veterans in my village [in the then German province of Upper Silesia, very close to the Polish border] formed an organization, similar to the Royal Canadian Legion, called “Kriegerverein“ or Soldiers’ Association. I am not aware that they had any social aspirations and can only assume that their get togethers were mainly to reminisce and serve as an excuse for a booze fest. There must also have been enough of musical talent among them to form a small brass band. While they must have played on other occasions, the only ones I can remember were at funerals for one of their former comrades. The band would lead the funeral procession from the home of the deceased, playing mournful music appropriate for the occasion. They were followed by an honour guard, usually made up of six veterans equipped with rifles. At the grave site, after the usual formalities and prayers had been observed and while the coffin was slowly being lowered into the grave, the band struck up the tune of “Ich hatt einen Kameraden” (The Good Comrade). While I can’t attest to the quality of their performance, it certainly gave the occasion a very dignified feeling. At that point in the proceedings, the honour guard would fire a triple salvo over the open grave. What I remember about the salute is that it sounded like a short machine gun burst, not like one unified volley. This, I presume, was due to the fact that some of the veterans were advanced in age and their reflexes varied. After the funeral service was over, the band would reassemble and march off playing lively marches. I am reasonably certain that they marched to the beer parlor to disassemble, where they paid tribute to their comrade by enjoying some alcoholic refreshments. After my father became a soldier during the Second World War, I remember he said that he was looking forward to joining the Kriegerverein after the war. Unfortunately for him, it came never to pass. [Note: My grandfather survived the conflict, but my father and his family became refuges after their area of Germany was ceded to Poland following the war.]

One of the highlights of village life was the annual “Heimatfest,“ an occasion similar to the garden parties held by some church parishes in Newfoundland. It was held on a summer Sunday afternoon. I was told later that I was taken to this occasion while I was still a toddler and, in order not to get lost or trampled, carried mostly in my mother’s arms. One of the activities taking place was the sale of tickets as a fundraiser for some charity. My parents, even though my father was unemployed at the time and money was tight, apparently agreed to buy a ticket and I was given the honour to pick it. But in the manner of small children, I grabbed a fistful instead of just one ticket. After the organizers retrieved all but one ticket stub and opened it, it turned out to be the main prize, which was a bag of approximately 50 kilograms of coal. Given the fact that the depression was still on and money was scarce, this ticket purchase turned out to be a good investment and a help to my family. It seems, however, that I must have used up my luck for the rest of my life, because I have not won anything since.

Everybody who owned a home or had some sort of yard kept not only chickens, but also geese and/or ducks. Not only were they appreciated as Sunday dinner, but their feathers were a valued commodity. In those days, where central heating was unknown and bedrooms were mostly unheated and very cold during the winter months, it was a matter of survival to have warm bedclothes. The answer to this fact of farm life was down-filled bedcovers, for which goose and duck feathers were essential. However, those feathers when plucked contained the calamus or quill, which was hard and would be prickly if not removed. The ideal time to have the calamus removed from the plucked feathers was during the long winter evenings, when outside work was at a standstill. Since this task was considered women’s work, five or six women in the neighborhood would get together and rotate from house to house until all the feathers harvested that fall and winter had been processed. With no radio in my early childhood and television still a thing of the future, entertainment had to be self-created. Once the village gossip, which was soon exhausted, had been exchanged, the storytelling would begin. It was an art form, and any woman who could spin a good yarn was in great demand. I recall one elderly woman, who was a particularly gifted storyteller, was part of our neighborhood group year after year. The women would get together after dinner and work at treating the feathers until 10 or 11 o’clock, sometimes even later. When I was old enough, I was allowed to listen to their tales until I was sent off to bed. Since my bedroom was adjacent to the kitchen, I requested that the door be kept ajar so I could continue to listen until I fell asleep. As far as I can remember, most of the stories were of the gruesome type – mostly about ghosts, appearances of the devil and dreams, especially of the nightmarish type, which I found fascinating. Of course, all the talking had to be done with bated breath so that the feathers would not be blown all over the kitchen! After the conclusion for the evening, liquid refreshments would be served, mostly of the benign type, but occasionally a bit more potent. Once the work in one house was completed, a party was thrown by the hostess, to which the husbands were also invited. These social gatherings tended to be fairly civil, but I can remember one occasion in particular where one of the ladies imbibed a bit more than usual. This led to a lot of loud singing and dancing into the early morning hours. While the women worked, three or four of the men would get together once a week for a game of cards. They played a game known as Skat, which is well known and played on a regular basis in Germany.

Since ours was a farming community without major Industries, it resulted in our area being underserved with modern amenities. Our village was connected to the electrical grid only around the late 1920s or early 1930s. Since we lived on a side street with only four homes, it meant we were not connected immediately. Part of the cost of erecting the poles and stringing the wires had to be borne by the homeowners. Therefore, it was only after my father found employment again and the worst of the depression was over that we could afford to get connected. That occurred in 1936 and I had started school. Consequently, until the age of six, I only knew lighting with kerosene lamps. The sole source of our news came from the local newspaper. I remember being all excited when my parents bought the first radio. What progress – we were finally connected to the world! Of course, the information we received was censored by the Nazis and, to a great extent, propaganda. But the main benefit of having a radio was entertainment, mainly in the form of popular music.

Love this blog!

One of these days I would love to read his memoirs. He e-mailed Dad a few chapters to read, I loved it, sooo interesting!

Keep of your wonderful writing!

Thanks, Jane! Dad would be thrilled in your interest and appreciation of his writing. We’ll see what we can do – his memoirs do need some serious editing though.

Awesome. Love the blog.

Thanks, Chris. I’m sure this Father’s Day was a tough one for you. Thinking of you.

Amazing. Thanks for this, Marina. I can hear him reciting this, too. I wish my own father had left memoirs.

Thanks, Chris. It warmed my heart to think you too could hear my father’s voice as you read his words. As for your father, he left a different kind of record – his paintings. And the cottage. And all the great memories (including mine of him).